|

Åke Bodén,

known for ”Åbosländan” (a dry fly) inherited the fly in 1902-04 from his

father Levi Bodén, who in his turn got it from Lars Piitsa, a Laplander

who lived 30 km upstream Övre Soppero on Lainio river. This particular

fly, already known to the Piitsa family for at least three generations,

and created no later than 1790, was probably tied around the middle of

the 18th century. Hook, from reindeer antlers decorated with cormorant

feathers, “tying thread” of reindeer tendon, fastened with resin or wax.

From the

19th Century, we have a more extensive documentation, and know that

during the Swedish agricultural era angling with some kind of fly was an

established method in parts of the country. The usual equipment was long

fishing pole with the line tied to the tip. The breakthrough for a more

modern form of fly-fishing came around 1814 when an English aristocrat

and sportsman, Richard Hutchinson, visited fishing spots in northern

Sweden. With him came British made flies - and the fly reel.

Still,

in the 1960’s when I became interested in fly-fishing, the British

influence was almost total. My favorite shop carried only flies of

British origin. Exotic patterns like Connemara Black, Hardy’s Favourite

and Silver Doctor crowded the shelves. After Hutchinson and far into

modern times British traditions dominated Swedish fly-fishing and

unfortunately gave it the reputation as an upper class sport.

Much water

has passed under the bridge since the 1960’s, and today fly-fishing has

become an every man’s sport. Along with rising interest, information

about fly-fishing has expanded tremendously. The study of insects and

their imitations has become a passion for many fly-fishers. No doubt, it

was easier to select a fly in the sixties, when weather conditions and

the time of day often were regarded as more important than insect

activities.

Nowadays,

most fishing and sports shops offer a confusing multitude of flies. In

addition, amateur tiers around our country produce thousands of flies.

The chance of creating a new fly pattern is practically non-existent.

What do fish think about our flies? Probably they do not think at all. A

fish functions mainly through reflexes and genetic behavior, although it

seems to have a kind of “food memory”, which to a fly-fisher may appear

as the result of a logical thought.

Roughly

speaking, there are two separate categories of flies. Imitations, which

are more or less exact replicas of the real thing, and lures, which

actually do not resemble anything edible, but still catch fish year

after year. Here my friend Jonas, a competent fly tier who, like most of

us, like most of us, does not care about conventions, but allows his

imagination to soar.

Counted

as a lure, this ”Tjernobyl Ant” is made of polycelon and has a number of

rubber legs that leave magical patterns on the water when retrieved in

short jerks. A mutant, although strange looking, has a strong attraction

to fish.

This is an

imitation beautifully tied by one of my talented friends. The hook

itself has a shape suggesting the curve of a mayfly’s body, giving the

wings a natural slant and the “legs” the right angle towards the

surface. Fortunately, you do not have to achieve an academic exam in

entomology in order to tie a fly that works - there are easier ways. See

below one of my favorite dry-fly patterns.

I call

it the minute-fly, since it seldom takes more than a minute to make. The

tying thread is grey, hackle and tail Blue Dun-colored, hook No. 12, 14

or 16. I tie in the hackle feather just behind the hook eye, wrap the

feather 3-4 sparse turns toward the hook bend, then 3-4 turns toward the

hook eye through the previous turns and then tie off. The fly floats

well and, although not an imitation, gives an illusion of a mayfly

riding high on the surface film.

Insects

are not developed to suit the hunting and eating habits of fish. Rather,

they have, according to the laws of evolution, developed in such a way

to make them hard to catch. To succeed, logically we should try to make

our imitations more visible than a natural insect. Consequently, it is

understandable why fish during a heavy fall of ants often prefer our

clumsy imitation, even if there are hundreds of naturals on the water.

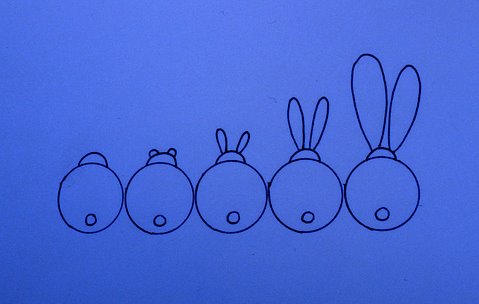

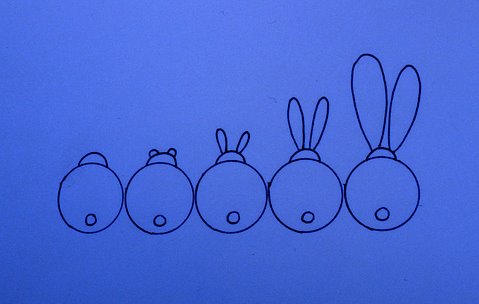

When

constructing a fly I have always believed in a slight exaggeration, here

illustrated by a gang of rabbits. The long ears are in drawings often

made extra long since they are so typical. In short, we make a more

distinct picture of the original. We immediately identify the drawing as

a rabbit, not because it is true, but because it accentuates a typical

characteristic. I imagine that a fish reacts in a similar way. Where a

perfect imitation is just one among many, the caricature gives an

immediate and positive impulse.

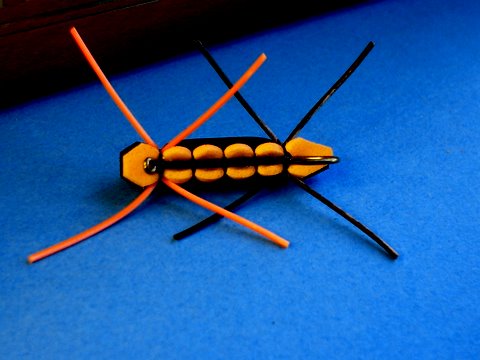

An

exaggeration may be that of a particularly profuse hackle, emphasizing a

special color, extra sheen to the fly body, or an overly marked

segmentation, as shown in this balsa fly. When it comes to streamers, a

protruding pair of eyes may give a tempting signal.

Articles

on fly-fishing often claim that a streamer is meant to copy a small fry.

Personally, I have never been altogether convinced that a sharp-eyed

trout actually would confuse a streamer with a small fish, even if the

imitation is cleverly made. Most of our streamers, like Appetizer,

Whiskey Fly, etc., actually do not represent anything at all, but have

qualities that attract the fish. The trout in the picture fell for a

Mickey Finn, a streamer where a bright red band between yellow fields

apparently affords a strong incentive.

All living

creatures have a relation to eyes. An eye may induce fear but, depending

on situation and circumstance, may also be alluring. During one season,

a group of fly-fishers made an interesting, if not very scientific test.

All were given three types of streamers. One without eyes, one with

painted eyes, and one with eyes made of glass beads. At the end of the

season, they put together a statistic on the amount of fish caught on

each type of streamer. See result below.

Cross-stream is the usual way to fish a streamer, always staying in

contact with the fly, making sure the curve of the line is not too wide

and letting the fly swing towards the bank. The strike often comes when

the line comes to a halt downstream. In slow current, it might be better

to retrieve the streamer in the ordinary way. And in the test? Well, the

streamer with no eyes came in third.

In still

water, “the countdown” method applies, since it gives you an idea at

what depth the fly moves. The moment it hits the water, you slowly count

to three before you start to retrieve, knowing that the streamer is

moving near the surface. At the next cast, you count to five seeking the

fish at a somewhat deeper level, etc. By the way, the streamer with

painted eyes came in second.

The

streamer with eyes of glassbeads was, according to the statistics, the

best by a certain margin. However, as mentioned before, this experiment

was not particularly scientific. Naturally, the success of a fly is

dependent on many other factors, not least how the fisher handles the

line. Using your fantasy is highly recommended when fishing a streamer.

Finally,

many fly fishers, including me, are overall incredibly conservative. On

a special occasion, we have had a good catch on a certain fly, and

stubbornly keep on trusting this particular pattern year after year. If,

by chance, we try a new fly, it is usually on a very hopeless day, when

the fish show no interest in anything at all. The untested pattern

seldom gets a chance to prove its potential when conditions are

favorable.

|